Should we fear the rise of the machines?

How will increased robotisation affect income, production and consumption? Will society benefit from the transition to automation in the long-run? Are humans destined for redundancy and poverty?

In his second blogpost on this subject our Director, Hector Pollitt explains why economists don’t always agree on the answers.

On New Year’s Day, still slightly bleary, I came across a piece in the Times by columnist Matt Ridley. The headline was ‘No need to fear the rise of the machines’ and the article contradicted much of what I said in a previous blog post here that suggested there was quite a lot to fear.

It doesn’t take much further searching to find similar disagreements online, see for example this excellent piece just before Christmas from Keynes biographer Robert Skidelsky.

It is generally agreed that Automation and Artificial Intelligence (AI) could wipe out 30% of existing jobs in the next 15 years.

For policy makers (at least the ones that still listen to economists) it must be of some concern that experts are reaching polar opposite conclusions about what will happen and what the correct policy response should be.

Such different conclusions

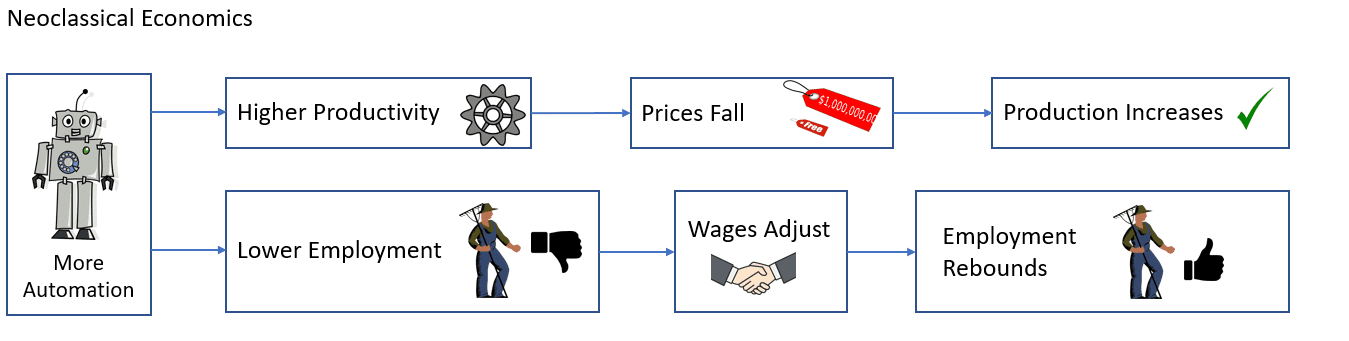

Sadly for an issue that is so important, the main schools of economics are making radically different predictions. Classical and neoclassical economists believe that the economy will sort itself out. Through their eyes economic growth is driven by supply-side factors, with price adjustments ensuring that demand is consistent with the optimal use of available resources (see diagram below):

As automation will improve productivity and potential output, these economists see a positive outcome from increased use of robots and AI. Empirically, this argument is backed up by ‘we’ve had technological progress before but it hasn’t wiped out all our jobs’. This is the view put forward by Matt Ridley and scenarios based on Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) modelling would find a similar outcome.

Economists from the mainstream New Keynesian school, which was developed from Real Business Cycle theory and underpins the DSGE models that central banks use, predict a similar long-run outcome but with possible increased unemployment rates in the short term while the economy adjusts back to equilibrium.

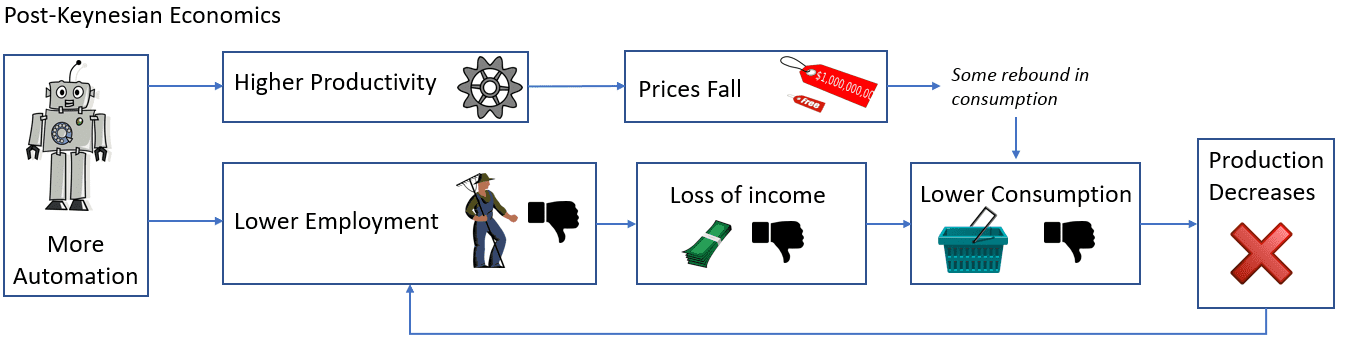

Post-Keynesian economists see things almost in reverse, however (diagram below). For them, aggregate demand is the driver of output and employment – with employment being the primary source of income that drives demand. The outcome from increased automation, as depicted by E3ME and other macro-econometric models, is potentially negative overall. Even if robots increase potential productivity, reduced income means lower demand for robots’ production.

The post-Keynesian argument that ‘this time is different’ to previous technological transitions has been overly simplified in some circles. As Skidelsky points out, the share of jobs at risk from automation is not that different to previous technological shocks, but it is the pace of change that matters.

If employed workers are not earning enough income to fund consumption then the positive long-run outcome may never be realised, unless the tech companies and a few very wealthy individuals (with assets far beyond anything seen before) find rather unbelievable ways to spend all the income they are earning.

Other philosophical differences

There are further important philosophical differences that become apparent when comparing the predictions of different economists in detail.

First, how inequality affects growth – post-Keynesians recognise that vast wealth accumulation by a small number of individuals could cause the economy to grind to a halt, while such an outcome is ruled out by assumption in neoclassical economics.

Second, the path dependence in post-Keynesian economics (i.e. what happens in the short term determines long-term outcomes) is completely missing from other approaches on the basis that the market will always be able to fix it.

So should policy makers fear the rise of the machines?

The truth (that will seem obvious to everyone except economists) is that we don’t know what will happen. We are heading towards uncharted territory and the world seems certain to look very different to how it does now. However, the pace of change means that policy makers will have to adjust quickly.

Most importantly, inputs are needed from all the different schools of thought, and also from the other social sciences. The financial crisis occurred in part due to relying too heavily on mainstream economics and all the assumptions it entails; if the same mistake is made again with automation, the impacts could be far, far worse.

This work was carried out under the Monroe project, which was funded by the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement 727114).